return to MSO history page

home

| Please note that this

chapter, now over 20 years old, will be superseded by a

much more exhaustively researched book on the orchestra's

history. I began work on this project after retiring

in 2018, with an eye towards completion before the

orchestra's 100th anniversary in 2026. I have left the

following largely unedited from 2000. However, in October

2020, I did make a few small changes - correcting a few

mistakes and clarifying a few things that have come to

light since I wrote this two decades ago. - M.A. October

2020 |

Second Movement

A Tale of Two Maestros,

1947-1961

by Michael Allsen

Prager's retirement

Dr. Prager publically announced his retirement early in the

1947-1948 season, stating that "the responsibility of directing

civic music would be placed on younger shoulders."

(Ironically, the orchestra's second Music Director, Walter

Heermann, did not possess "younger shoulders"—he was only a year

or so younger than Prager!) I originally suspected that his

retirement might have been in part due to bad feelings between

Prager and Civic Music: things like the Kunrad Kvam affair

of 1946, and other skirmishes with various musicians and board

members. In talking to those who knew him, though, I found

no evidence of this. He seems merely to have wanted to

retire to a more relaxed life. At his farewell

banquet in June 1948, Prager explained: "I have been asked

privately why I am retiring. I have no reason to retire—no

complaints about work or salary or anything. I am just

putting into effect a youthful ambition...that whenever I am quite

happy with my work and with my life, I won't gamble with

happiness. Then, if I am financially able to so, I shall

refuse to take the chance of destroying that happiness."

The local press was lavish in their praise of the

retiring Prager. A State Journal editorial early in

the year commended him for "...a job splendidly done, not only for

Madison, but for others who have envied our lot, and can copy our

recipe for its making." On the day of Prager's final

concert, William Doudna of the State Journal wrote:

"Prager's career here has been that of a genius...in the sense

that it is a rare man who can weld amateur, professional, and

semi-professional musicians into a homogenous whole. And he

has poured love into his work - a love for music, the kind that

requires that it be shared with as many as can come within the

sound of it."

Prager's farewell

program, May 23, 1948, UW Stock Pavilion

Prager's

farewell concert took place on May 23, 1948: a performance

of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis given to a crowd of over

2000 at the Stock Pavilion. It was reportedly a fine

performance, but also an tearful event: Prager was

reportedly so emotional as he said a few words after the concert

that only the first few rows of the audience heard him. The

State Journal review on the following day includes a photo

of a visibly choked-up Prager shaking hands with a chorus member,

one of hundreds of musicians and audience members who thanked him

after the concert. [There is an postscript to this

concert...over 65 years later! A recording of this program

surfaced in 2013. See Historical

Recordings for details and audio samples.]

Prager's

farewell concert took place on May 23, 1948: a performance

of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis given to a crowd of over

2000 at the Stock Pavilion. It was reportedly a fine

performance, but also an tearful event: Prager was

reportedly so emotional as he said a few words after the concert

that only the first few rows of the audience heard him. The

State Journal review on the following day includes a photo

of a visibly choked-up Prager shaking hands with a chorus member,

one of hundreds of musicians and audience members who thanked him

after the concert. [There is an postscript to this

concert...over 65 years later! A recording of this program

surfaced in 2013. See Historical

Recordings for details and audio samples.]

Prager's retirement seems to have been happy: he and his wife

Frances moved to her native Argentina in September of 1948, and

apparently enjoyed themselves, making several trips to

Europe. Prager remained in close contact with friends in

Madison, and after the tradition of the times, some of his letters

were published in the local papers. Letters he wrote to

Alexius Baas and Betty Cass in the spring of 1949 are filled with

details of life in Carlos Paz, a town near Buenos Aires,

appreciative descriptions of local food and wine, and plans for a

European vacation. He retained a great affection for Madison

- according to his former piano student Gerald Borsuk the Pragers'

home in Argentina was named "Villa Madison." Prager

had originally been engaged to teach at the University in the

spring of 1949, but he wrote that "commitments" would keep him in

South America," and declined the University's offer.

Though he did conduct orchestras in Argentina, I suspect his

"commitments" had more to do with an enjoyable retirement than

professional engagements!

In 1951, Prager became the conductor of the Philharmonic

Orchestra of the Agentinian state of Punilla, but he did return to

Madison twice to teach at the University. For most of the

1951-1952 school year, he taught conducting at the UW School of

Music. He returned again in the fall of 1953 through early

1954, his last visit to Madison to give eight lectures on the

"Masterworks of Opera" at the UW Extension, and to do a series of

live music appreciation programs on WHA-TV. The

Pragers continued to travel in Europe and South America after

this, and Prager continued to teach privately and as a professor

at the University of Córdoba into his 80s. He died at age 85 in

April of 1974‚ news which did not reach Madison for six

months. The MCMA had written to see if he would be

interested in traveling to Madison to take part in the orchestra's

fiftieth anniversary in 1976-1977, only to find that he had passed

away. At a MSO concert on January 31, 1976, Roland Johnson

programmed a transcription of Bach's chorale prelude In Our

Hour of Deepest Need as a tribute to the orchestra's first

conductor.

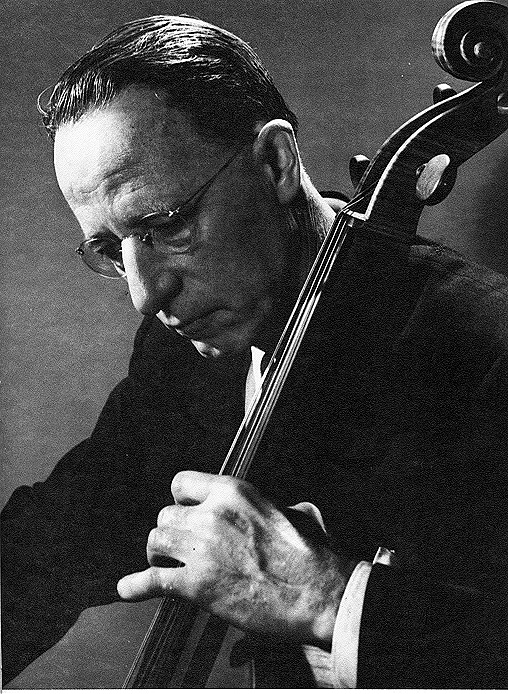

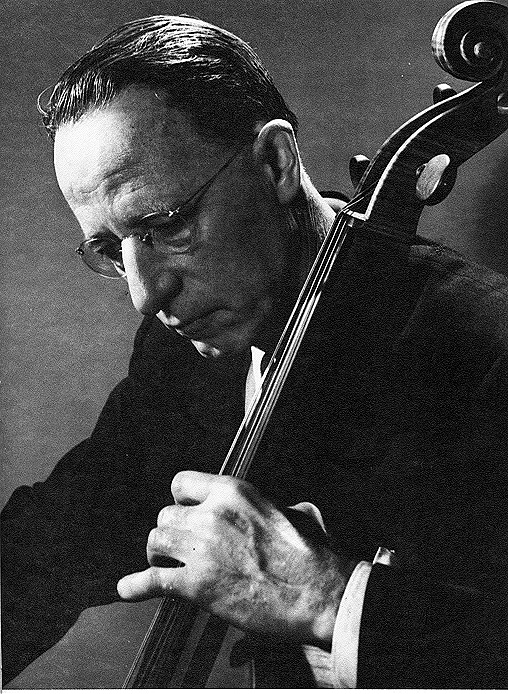

Walter Heermann

When Prager announced his

retirement, the MCMA board started the search for a new Music

Director. In reality, though, Prager had a great deal of

influence over the process, and Walter Heermann, MCMA's second

Music Director was his hand-picked successor. Prager and

Heermann had met when both were teaching at the University's

Summer Music Clinic. Like Prager, Heermann was German.

Born in Frankfurt in 1890, Heermann came from a musical

family. His father, Hugo Heermann, was a virtuoso violinist

who was a close friend and associate of Brahms - the composer

often visited their home when Walter and his older brother Emil

were young children. His debut performance as a cellist was

with his father and was conducted by Richard Strauss. In

1906, Hugo Heermann came to the United States and his sons Walter

and Emil, a violinist, followed him in 1907. In 1909,

conductor Leopold Stokowski invited Hugo Heermann to become

concertmaster of the newly reorganized Cincinnati Symphony

Orchestra, and his sons took positions in the orchestra as

well. Though Hugo Heermann return to Germany in 1911,

both of his sons remained in the orchestra for nearly 40

years. Emil eventually followed his father as

concertmaster. Walter started as last chair cello in 1909,

but eventually became the orchestra's principal cellist. In

a 1949 interview, he noted that: "I think that I'm the only

cellist who occupied all of the chairs - from sixth to first."

When Prager announced his

retirement, the MCMA board started the search for a new Music

Director. In reality, though, Prager had a great deal of

influence over the process, and Walter Heermann, MCMA's second

Music Director was his hand-picked successor. Prager and

Heermann had met when both were teaching at the University's

Summer Music Clinic. Like Prager, Heermann was German.

Born in Frankfurt in 1890, Heermann came from a musical

family. His father, Hugo Heermann, was a virtuoso violinist

who was a close friend and associate of Brahms - the composer

often visited their home when Walter and his older brother Emil

were young children. His debut performance as a cellist was

with his father and was conducted by Richard Strauss. In

1906, Hugo Heermann came to the United States and his sons Walter

and Emil, a violinist, followed him in 1907. In 1909,

conductor Leopold Stokowski invited Hugo Heermann to become

concertmaster of the newly reorganized Cincinnati Symphony

Orchestra, and his sons took positions in the orchestra as

well. Though Hugo Heermann return to Germany in 1911,

both of his sons remained in the orchestra for nearly 40

years. Emil eventually followed his father as

concertmaster. Walter started as last chair cello in 1909,

but eventually became the orchestra's principal cellist. In

a 1949 interview, he noted that: "I think that I'm the only

cellist who occupied all of the chairs - from sixth to first."

Descriptions of Heermann's playing from those who knew him are

very complimentary - he was obviously a fine player who had an

unbelievably large sound. James Crow, who played viola in

the Civic Symphony under both Heermann and Roland Johnson,

remembers hearing a concert in the 1960s, when Heermann was asked

to play principal cello in the University Symphony.

According to Crow, "There were a lot of cellos there, but all you

heard was Walter." I have heard one recording of

Heermann as a soloist, a rare LP that has a series of live

performances of works by Madison composer Sybil Hanks.

Heermann premiered Hanks's Meditation at this program, and

it is a lovely performance with a very large and deep sound.

[This performance can be heard on the Historical

Recordings page.] Though he only played one concerto

with the orchestra - he and his brother Emil performed Brahms's

"double" concerto to close his first season in Madison - Heermann

played chamber music in Madison throughout his tenure as Music

Director and well into his retirement years.

The other side of Heermann's musical career was conducting.

He had fine models: at Cincinnati, he worked under both

Leopold Stokowski and Eugene Goosens. By the 1930s, he was

frequently filling in as a guest conductor, and had the title of

Assistant Conductor when he retired from the

orchestra. (He returned to Cincinnati at least

once after taking the position in Madison to conduct the orchestra

there.) He had occasional guest conducting engagements, and

served as the director of the Charleston (WV) Music Festival from

1931-1942. Again, those who played under his baton are

complimentary: Heermann knew his scores very well and was

extremely effective in communicating his musical ideas. When

he retired, he donated his entire collection of orchestral music

to the MCMA, and a even quick glance through the scores in this

collection shows evidence of his close study and preparation of

each piece.

Why did Heermann, who was nearly 60 when he moved to Madison,

take this position? Roland Johnson, who had been a protégé

of Heermann's in Cincinnati, feels that it was at least partially

a reaction to a changing situation there. Emil Heermann had been

moved (unwillingly) out of the Concertmaster's chair a few years

earlier , and Johnson felt that Walter Heermann saw "the writing

on the wall" regarding his own position as principal

cellist. However, Madison also provided a chance to

conduct—something that had been more and more part of his

activities with the Cincinnati Symphony during the 1940s.

The Madison Civic Symphony, though not a professional orchestra,

had been built by Prager into a respectable amateur ensemble

capable of tackling a variety of challenging works.

At the close of his first season, in June 1949, Heermann

presented an enthusiastic report to the annual meeting of the

MCMA's membership:

"Quite often in these past months, people have asked me: 'Well,

have you found enough to do in Madison to keep you busy?' My

answer is: 'enough to fill up an entire scrapbook with one

season's activities, which never happened before!' Indeed,

it was fortunate that my added classes at the University of

Wisconsin did not start until February, so that there was time to

get used to my new work as Supervisor at our Vocational School as

well as directing our Civic Music forces...

"Dr. Prager's final and friendly counsel was: 'Now don't change

anything!' And generally we did adhere to the well

established routine of Civic schedule. Quite naturally,

when a man of his caliber's achievements leaves for good, you

will find that a number of members leave with him, and so with

us--a somewhat smaller orchestra and a quite diminished chorus

reported last fall - so one thing was almost had to change was

the choral repertoire, substituting, not lighter perhaps, but

shorter a capella choruses, cantatas, etc., for the usual and

annual big oratorio or opera. In the long run, this

procedure, including an added solo concert for the Chorus,

actually gave them a wider range of activities, fitting with

their size and capabilities. We did keep up the annual Messiah

performance just before Christmas and again, this concert drew a

capacity crowd. I am quite aware that some of our older

Chorus members have missed the glamour of King David and

Samson and Delilah gala nights, and it is also obvious

that the don't recall one feature of those past glories.

The Missa Solemnis and like performances were made

possible through Dr. Prager drafting as 'guests' almost every

good voice from other choral organizations all over town and

University, a process I have no access to nor inclination for -

I can only tell this to our ambitious souls: Give us time

and a better Chorus, and you shall have Beethoven's Ninth or

Bruckner's Mass in no time!"

Heermann continued, noting his plans for the next season (a Young

People's Matinee), and lauding "our best friend," the Vocational

School and its Director, Dr. Bardwell. He also outlined

several goals for the long term:

"Programs: We will continue to present the best there

is in orchestral and choral repertoire. Soloists:

We are going to feature young American artists of proven worth,

but just before they rate a New York manager and a large

fee. Attendance: we played to about 6500

people last year, which is not impressive. We hope to

improve this record by advertising more than we have been... Finances:

Our big wish came true—we finished in the black—in fact, we don't

recognize red as a financial color any more, but we do hope to

finish next season with enough surplus to for a reserve fund or to

spend same in a way where it will be a real help for Civic Music."

Heermann's personality has generally been described by those who

knew him as "laid back" - a distinct change from Prager's

tightly-disciplined approach. Though he could occasionally be

sharp and sarcastic with individual players, in general he was quite

well-liked by members of the orchestra and chorus. James and

Ann Crow report that it was a great deal of fun to play in the

orchestra during the 1950s, but that Heermann was very relaxed about

attendance at rehearsals, and that the musical quality occasionally

suffered. Even performances in the Heermann years were

sometimes rough-and-ready. Ann Crow, who played clarinet

during this period, recalled one near-disastrous performance of the

Nutcracker Ballet:

"They didn't have anybody who was actually a bass clarinetist to

play the Nutcracker - you know the part [in the Dance

of the Sugar Plum Fairies] 'ta-da-da-da-dah.' So they asked

me if I could play the bass clarinet. I said that I didn't

know, I'd never tried, but that if they gave me the the instrument

for a couple of weeks, I could probably play that short little

solo... Anyhow, Walter was conducting, and we had a pair of very

excellent dancers from New York...who were to do the Dance of the

Sugar Plum Fairies. They came on stage, and I played my

solo--'ta-da-da-da-dah' and then nothing happened. There was

a pianist who was playing the celeste part, and she was looking

off to the stage at the dancers. So Walter started

whistling..."

Gerald Borsuk - for many years an oboist in the Civic Symphony, and

a piano soloist on two occasions - recalled a similar incident in a

performance of the Gershwin Concerto in F, in which he was

the soloist. One of the most dramatic moments in the concerto

is punctuated by a great crash on the gong. Heermann borrowed

a gong from Chicago for this performance, and when the climactic

moment came gave a large and dramatic cue...to absolute

silence! Lest these anecdotes leave the wrong

impression, it should be noted, that the Civic Symphony's

performances under Heermann were generally quite good. Though

Heermann was never able to recruit quite enough string players to

adequately balance the brass and woodwinds, recordings of the

orchestra from the 1950s reveal an ensemble that is generally

accurate and quite musical, if clearly a largely amateur group.

Civic Symphony and Chorus in rehearsal under Heermann, mid

1950s

The Madison Civic Symphony and Chorus in the

1950s.

With Heermann's first season in 1948-1949, there was a marked

change in the character of the orchestra's repertoire.

Heermann had come to Madison after nearly forty years in one of

America's leading professional orchestras, and the Civic

Symphony's programming began to resemble that of a professional

orchestra. Where Prager had favored large "extravaganzas"

with multiple groups and sometimes a dozen or more works,

Heermann's orchestra concerts seldom featured more than three or

four pieces, most often in a format that is now more or less

standard: an opening overture, followed by a concerto, with a

larger symphonic piece after intermission. Not

surprisingly, given Heermann's background, the orchestra's

repertoire also took on a distinctly German-Austrian character,

and the works of Brahms were given pride of place. All four of

Brahms's symphonies were performed during his tenure, as well as

both piano concertos, the violin concerto, the "double"

concerto, and choral works like the "alto rhapsody," Nanie

and the German Requiem. Beethoven, Schubert,

Haydn, Mozart, Handel, and Bach were also heavily featured in

these years. This is not to say that Heermann neglected

other "non-German" repertoire, however. The orchestra's

programming included works by composers as wide-ranging as

Milhaud, Sibelius, Kodaly, and even Monteverdi.

One highlight of the 1950-51 season, the orchestra's 25th

anniversary, was the first American performance of Oskar Hagen's Concerto

Grosso. Hagen, an Art History professor at the

University was also a composer and an expert on the works of

Handel. (Before emigrating to the United States in 1925,

Hagen had been director of the Göttingen Handel Festival, and had

edited many of of Handel's vocal works.) He had been a

supporter of the MCMA from its earliest years, and had even

composed a work dedicated to Dr. Prager, the Choral Rhapsody,

which was premiered by the Civic Symphony and Chorus in

1944. A rare recording of the Civic Symphony's performance

of the Concerto Grosso reveals this to be a very

well-crafted work, very much inspired by Baroque style. [This work

can be heard on the Historical

Recordings page.]

Heermann was obliged to spend some years rebuilding the Civic

Chorus. Many longtime members had retired with Prager, and

there had also been a loss of membership a few years earlier, when

several singers from the Chorus left for the Philharmonic

Chorus. Heermann featured the Civic Chorus every spring in a

choral concert. For the first few years, these programs

contained a variety of works in the older tradition of Prager,

usually with piano accompaniment. Increasingly though,

Heermann used the spring choral concert for larger, more ambitious

works "the usual and annual big oratorio" of years gone by:

Mendelssohn's Elijah (1951), the Brahms German Requiem

(1952), Verdi's Requiem (1954), Rossini's Stabat Mater

(1955), Orff's Carmina Burana (1956), Beethoven's Mass

in C Major (1957) and the Kodály Te Deum (1961).

The annual Messiah tradition begun by Prager continued

through the 1950s. By the time Heermann took over in 1948,

the December Messiah concert was almost sacrosanct in

Madison, and Heermann continued to conduct the oratorio much as

Prager had: with full Romantic orchestra and the by-then

traditional cuts. Heermann tinkered with the tradition,

however; in particular, spreading the arias out among

as many local singers as possible (some Messiah

performances in this period featured nearly a dozen soloists). In

December 1957, Heermann programmed what was billed as the Civic

Chorus's first "complete" Messiah. This uncut

version of the work was spread out over two performances, one in

the afternoon, and one in the evening.

While Prager had been able to mount several operas in the 1930s,

MCMA did not sponsor any fully-staged operas during the 1940s and

1950s. (Staged opera performances would return in the 1960s

with the arrival of Roland and Arline Johnson, and the creation of

the Madison Civic Opera Guild.) However, MCMA did present

several concert versions of operas under Heermann's

direction. These performances, which sometimes took the

place on the spring choral program, featured local singers in the

solo roles. MCMA presented four of these concert operas in the

late 1950s: Cosi fan tutte (1956), Act III of Die

Meistersinger (1957), Ariadne auf Naxos (1958),and Cavalleria

rusticana (1959).

Youth concerts had been part of the orchestra's programming in

the early years, but during the late 1930s and early 1940s, this

function was largely taken over by the WPA-funded Madison Concert

Orchestra. Heermann reinstituted regular "Young People's

Matinees" in the 1949-1950 season. Heermann's youth concerts

(undoubtedly modeled upon concerts he had conducted in Cincinnati)

were aimed at education and featured pieces that were designed to

be entertaining to a very young audience. Innovation was

very much a part of these concerts, as in the first program when a

local art teacher, David Carman, sketched a series of abstract

images on an overhead projector as the orchestra played a Weber

overture. MCMA worked closely with local teachers to run an

essay contest in connection with these programs. Most

importantly, they also featured children themselves: small

ensembles from various studios, and soloists selected through an

MCMA-sponsored "talent contest." These matinees were

tremendously successful, beginning a tradition of educational

outreach that continues fifty years later.

Another innovation introduced by Heermann in his last years was

an annual Pops concert. Prager had occasionally programmed

"popular concerts" in his earliest seasons, but these consisted of

little more than a collection of movements from works done in the

season, repeated "by popular demand." Heermann had wanted to

program a series of Pops program from the very start of his tenure

in Madison, and was working from very different model: the famous

Boston Pops had established a distinctly American style of concert

with light classics and orchestral arrangements of popular styles,

and Heermann had been involved with Pops concerts in

Cincinnati. The first Pops program, or "Orchestra Gala," on

April 30, 1960 at the Loraine Hotel, was very much in this mold,

presenting a series of very light and entertaining works in a

socially informal setting. The first program drew on works

by Johann Strauss, Suppé, and the most well-known of American

light composers, Leroy Anderson. This program was run as a

benefit by the Women's Committee, and was a great financial and

social success, though some community members were upset that the

Civic Orchestra was charging for tickets. Heermann's final concert

as the orchestra's Music Director was the second Pops program, on

April 29, 1961.

The Orchestra and the Community

In reading between the lines of Board minutes during the Prager

years, it seems obvious that while the MCMA Board was nominally in

charge, Prager and the Vocational School's Alexander Graham made

most of the real decisions. The Board, which expanded from

20 members in the early 1940s to 30 members in the 1948-49 season

began to take a much stronger hand in running the affairs of the

MCMA during the 1950s. The MCMA Board was led by a series of

local women from the community all through Heermann's tenure:

Florence Anderson (1946-49), Stella Kayser (1949-51),

Eleanor Carter (1951-53), Eugenie Mayer Bolz (1953-59), and Viola

Ward (1959-61). The membership of the board was largely made

up of women who volunteered to run the support activities of the

orchestra, from marketing and fundraising to answering phones and

stuffing envelopes. Helen Supernaw, who served on the Board

throughout this period was particularly instrumental in day-to-day

operations: in essence, she was the entire administrative

staff of MCMA, running the office, overseeing printed programs,

and taking care of countless details, all as an unpaid volunteer.

The organization's budget was never large in the 1950s - total

expenditures never exceeded $6000 per season - but through the

Board's efforts, MCMA was able to maintain the tradition of free

concerts throughout the 1950s. With well-attended concerts

and outreach programs like the annual Young People's Matinee, the

orchestra and chorus were very much a part of Madison's cultural

life, and were frequently mentioned with pride in Chamber of

Commerce pamphlets, and other literature promoting the city.

Heermann was a strong believer in the American Symphony Orchestra

League, and MCMA joined the ASOL in his first season as Music

Director. He would attend the annual convention, or would

arrange for one or two Board members to attend each year.

Viola Ward and Helen Supernaw attended one such meeting in 1954,

and returned convinced that some sort of auxiliary organization

could be be useful to the MCMA. The Women's Committee

organized in 1956 proved to be a success: running social

events to benefit the orchestra and beginning a series of

educational efforts. Later reorganized as the Madison

Symphony Orchestra League, this vital organization continues to

provide invaluable volunteer and financial support today.

One of Madison's most rancorous political issues in the 1950s was

the ultimately unsuccessful attempt to build a Frank Lloyd

Wright-designed community center. The original design

included a civic auditorium, and as early as 1947, local aldermen

had approached MCMA for support in pushing the project through.

Heermann and other Civic Music representatives were active

throughout the late 1950s on city committees devoted to the

Community Center issue. In the end, this issue was tabled -

for nearly 30 years! - when community support was lacking.

The present Monona Terrace is of course the result of the

successful political efforts in the late 1980s and early 1990s to

resurrect Wright's design, but reconfigured as convention center.

In the meantime, the orchestra continued to search for a

performing space. The Masonic Temple Auditorium had been the

primary venue for Civic Orchestra and Chorus concerts since the

late 1930s. It is a visually impressive space, and its

resonance makes it admirably suited for Masonic speeches and

ritual, but the Temple was an acoustical nightmare for orchestra

players. At the beginning of the 1953-54 season, Heermann

moved concerts back to the orchestra's first home, the Central

High School Auditorium. Heermann worked valiantly in the

1950s to make acoustical improvements to this space and to extend

the stage to accommodate larger choral and orchestral

forces. (Unlike his predecessor, Heermann never programmed a

concert in the Stock Pavilion, arguably the best acoustical space

in town at the time.) Central High School Auditorium (later

MATC Auditorium) would remain the orchestra's home until the

opening of the Oscar Mayer Theatre in 1980.

Concert in the Masonic

Temple Auditorium, May 8, 1949:

Brahms's Alto Rhapsody, with soloist Nan

Merriman.

Towards a Professional

Ensemble

Towards a Professional

Ensemble

One of the more controversial moves during Heermann's tenure had

little to do with the music itself, but had an enormous long-term

impact on the course of the orchestra's growth. Since the

very beginning, the Civic Symphony had been largely a volunteer

organization. A few musicians did indeed get paid by the

Vocational School: concertmaster Marie Endres was paid a

relatively modest sum per service, which included her supervision

of hundreds of string rehearsals over the years , and the

principal cellist and librarian also received a small

honorarium. The few Musician's Union members who performed

with the Symphony received a small payment for performances.

We may speculate that the occasional "ringers" brought in by

Prager for performances through the 1930s and 1940s - mostly

professional players from Milwaukee - may have received some sort

of payment, though no record exists in the MCMA financial

records. (There had undoubtedly been some sort of private

arrangement.) There were also occasional WPA players in the

orchestra, who performed as part of their federally-funded

activities. The vast majority of players in the early 1950s

were still rehearsing and performing for free, however.

The issue of paying the regular members of the orchestra has it

roots in the 1950-51 season. At this point, the only pay

available to most players was free babysitting arranged by the

MCMA: available to those members (mostly women and the several

husband-wife pairs who played in the orchestra) who could not

otherwise play for performances. Heermann reported

that the draft (now in in full force during the Korean War) was

beginning to have an impact on the membership of the orchestra,

and asked the Board for permission to hire substitute

players. After some discussion, the Board tabled the matter

of establishing a regular fund to pay substitutes, but did allow

Heermann some discretionary funds. The matter

remained officially tabled for the next several years but Heermann

apparently used rather wide discretion in bringing in players,

particularly in the string section, the Civic Symphony's weak link

during this period. It also became traditional

for a few of the prominent players in the orchestra - the

principal strings and the principal trumpet - to receive a bonus

check from the MCMA at Christmas.

By the end of the 1950s, the majority of orchestra members were

in fact being paid for performances, though not by the MCMA.

Members of American Federation of Musicians, Madison Local 166

received a performance fee (about $7.00) which was funded by the

Music Performance Trust Fund. The MPTF, a fund created from

royalties paid to the national union was used (and is still used)

to support live performances. Even this relatively

small amount caused some controversy within the orchestra and

among its supporters. Gerald Borsuk relates that there was

occasionally friction between those orchestra members who were

being paid and those who weren't. Memories of the

Prager years were still fresh in the minds of many longtime

supporters, who held to his ideal of civic music as a "fine

democratic effort," created for the sheer love of music.

James Crow noted that there were several vocal opponents to

allowing pay of any kind to the members of the

orchestra. It was not until long after Heermann

retired that the orchestra concluded its first Master Agreement

with the MCMA, but the 1950s saw first steps towards putting the

Madison Symphony Orchestra on a fully professional footing.

Another Transition

In early 1960, the Vocational School caused a flap locally when it

announced that Heermann had to leave his post. According to

agreements reached in the earliest years of the MCMA, the

orchestra's Music Director was paid by the Vocational School, and

Heermann had by then reached the mandatory retirement age of

70. There was an outcry among musicians and community

members, with petitions and open letters protesting the Vocational

School's policy. In March of 1960, the Vocational School and

MCMA reached a cordial agreement that allowed Heermann to stay on

for one additional year, through the end of the 1960-61

season. This would allow the MCMA some fourteen months to

conduct a search for Heermann's successor. However,

once again, the orchestra's Music Director chose his own

successor. According to James Crow, "Walter stayed on that

extra year to allow Roland [Johnson] time to get here." - a story

confirmed by Mr. Johnson.

At his final Board meeting, Heermann wryly misappropriated a

famous quote, remarking that: "Old conductors never die...they

just quietly leave town." Despite this, Heermann

settled down to a quiet retirement in Madison. He continued

to play chamber music with friends and to teach private cello

students in Madison and Milwaukee throughout the 1960s. He

died in Madison on June 10, 1969 after a brief illness. As

he would do for Prager several years later, Roland Johnson

programmed a special work in memory of Heermann at an orchestra

concert the next season: Barber's Adagio for Strings.

Each of the four men who have led the Madison Symphony in the

last 75 years has made a unique and lasting contribution to that

history. Naming Sigfrid Prager as our Founding Father is no

exaggeration. Prager's work carried the orchestra through

its first twenty-two seasons - through enthusiam, and, at times

seemingly, through sheer force of personality. If Walter

Heermann played a somewhat more reserved role in his thirteen

seasons, it was a no less significant contribution. Under

his leadership, the orchestra's programming acquired a degree of

"big city" polish, and the orchestra itself began to make the

transition from an amateur group to the professional ensemble that

exists today.

---

©2000 by J. Michael Allsen - revised 2015 and 2020.

last update: 10/17/20

Prager's

farewell concert took place on May 23, 1948: a performance

of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis given to a crowd of over

2000 at the Stock Pavilion. It was reportedly a fine

performance, but also an tearful event: Prager was

reportedly so emotional as he said a few words after the concert

that only the first few rows of the audience heard him. The

State Journal review on the following day includes a photo

of a visibly choked-up Prager shaking hands with a chorus member,

one of hundreds of musicians and audience members who thanked him

after the concert. [There is an postscript to this

concert...over 65 years later! A recording of this program

surfaced in 2013. See Historical

Recordings for details and audio samples.]

Prager's

farewell concert took place on May 23, 1948: a performance

of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis given to a crowd of over

2000 at the Stock Pavilion. It was reportedly a fine

performance, but also an tearful event: Prager was

reportedly so emotional as he said a few words after the concert

that only the first few rows of the audience heard him. The

State Journal review on the following day includes a photo

of a visibly choked-up Prager shaking hands with a chorus member,

one of hundreds of musicians and audience members who thanked him

after the concert. [There is an postscript to this

concert...over 65 years later! A recording of this program

surfaced in 2013. See Historical

Recordings for details and audio samples.] When Prager announced his

retirement, the MCMA board started the search for a new Music

Director. In reality, though, Prager had a great deal of

influence over the process, and Walter Heermann, MCMA's second

Music Director was his hand-picked successor. Prager and

Heermann had met when both were teaching at the University's

Summer Music Clinic. Like Prager, Heermann was German.

Born in Frankfurt in 1890, Heermann came from a musical

family. His father, Hugo Heermann, was a virtuoso violinist

who was a close friend and associate of Brahms - the composer

often visited their home when Walter and his older brother Emil

were young children. His debut performance as a cellist was

with his father and was conducted by Richard Strauss. In

1906, Hugo Heermann came to the United States and his sons Walter

and Emil, a violinist, followed him in 1907. In 1909,

conductor Leopold Stokowski invited Hugo Heermann to become

concertmaster of the newly reorganized Cincinnati Symphony

Orchestra, and his sons took positions in the orchestra as

well. Though Hugo Heermann return to Germany in 1911,

both of his sons remained in the orchestra for nearly 40

years. Emil eventually followed his father as

concertmaster. Walter started as last chair cello in 1909,

but eventually became the orchestra's principal cellist. In

a 1949 interview, he noted that: "I think that I'm the only

cellist who occupied all of the chairs - from sixth to first."

When Prager announced his

retirement, the MCMA board started the search for a new Music

Director. In reality, though, Prager had a great deal of

influence over the process, and Walter Heermann, MCMA's second

Music Director was his hand-picked successor. Prager and

Heermann had met when both were teaching at the University's

Summer Music Clinic. Like Prager, Heermann was German.

Born in Frankfurt in 1890, Heermann came from a musical

family. His father, Hugo Heermann, was a virtuoso violinist

who was a close friend and associate of Brahms - the composer

often visited their home when Walter and his older brother Emil

were young children. His debut performance as a cellist was

with his father and was conducted by Richard Strauss. In

1906, Hugo Heermann came to the United States and his sons Walter

and Emil, a violinist, followed him in 1907. In 1909,

conductor Leopold Stokowski invited Hugo Heermann to become

concertmaster of the newly reorganized Cincinnati Symphony

Orchestra, and his sons took positions in the orchestra as

well. Though Hugo Heermann return to Germany in 1911,

both of his sons remained in the orchestra for nearly 40

years. Emil eventually followed his father as

concertmaster. Walter started as last chair cello in 1909,

but eventually became the orchestra's principal cellist. In

a 1949 interview, he noted that: "I think that I'm the only

cellist who occupied all of the chairs - from sixth to first."

Towards a Professional

Ensemble

Towards a Professional

Ensemble