return to MSO history page

home

| Please note that this

chapter, now over 20 years old, will be superseded by a

much more exhaustively researched book on the orchestra's

history. I began work on this project after retiring

in 2018, with an eye towards completion before the

orchestra's 100th anniversary in 2026. I have left the

following largely unedited from 2000. However, in October

2020, I did make a few small changes - correcting a few

mistakes and clarifying a few things that have come to

light since I wrote this two decades ago. - M.A. October

2020 |

Third Movement

The Johnson Era, 1961-1994

by Michael Allsen

From Walter Heermann to Roland Johnson

In early 1960, Walter Heermann, who was in his eleventh season as

Music Director of the Madison Civic Music Association (MCMA) - the

umbrella organization for the Madison Civic Symphony and the

Madison Civic Chorus - was informed that he would have to leave

his post at the end of the 1959-1960 season. Since 1928,

MCMA's Music Director had been paid by the Madison Vocational and

Adult School (later MATC), and Heermann had reached the Vocational

School's mandatory retirement age of 70. After a very public

outcry by MCMA's board and supporters, the Vocational School and

MCMA reached a cordial agreement that allowed Heermann to stay on

for one additional year, through the end of the 1960-61

season. This would allow the MCMA some fourteen months to

conduct a search for Heermann's successor. A search

committee was appointed in March of 1960, and there were several

candidates discussed by the MCMA Board in the summer of

1960. As these informal inquiries were being made, however,

Heermann was making calls to a former student named Roland

Johnson, who was then teaching at the University of Alabama.

Johnson was not officially mentioned as a candidate until

September, but it is clear that Heermann had Johnson in mind as a

possible successor from the first.

Johnson was initially quite hesitant about leaving a secure

academic position at Alabama, but he was also well aware of

Madison's reputation as an excellent place to live and raise a

family: it was this very period that Life and other

national magazines began to praise Madison as one of America's

most "livable" cities. And Heermann was persistent -

according to Johnson: "Walter kept after me...he had to work

hard to talk me into it." There was also a delayed promotion

at Alabama that convinced Johnson that it might be time for a

change. He and his wife Arline visited Madison over

Thanksgiving weekend in 1960, and the Board almost immediately

offered him the position. By January of 1961, Johnson had

accepted, and agreed to begin as MCMA's Music Director for the

1961-62 season, the first year of a remarkable 33-year tenure.

Heermann remained in Madison until his death in 1969, but

remained quietly in the background as Johnson put his own mark on

MCMA. Johnson remembers that the two of them performed

together for the very first Women's Committee meeting of the

1961-62 season.

Roland Johnson

Roland Johnson

The orchestra's third conductor was born in Johnson City,

Tennessee in 1920. He studied violin as a child, and was

talented enough to win a statewide prize at age 15. He

received a scholarship to the Cincinnati College of Music, and

studied violin with Emil Heermann. He became even closer to

Emil's brother, Walter, who conducted the college's orchestra, and

became something of a protégé and assistant conductor of the

orchestra. The conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony

Orchestra, Eugene Goossens, offered Johnson a position in the

orchestra in 1941, but the war intervened and Johnson enlisted in

the Navy. He wryly notes that his "great contribution to the

war effort" had more than a little to do with his musical

training. Johnson was in charge of training sonar operators

for anti-submarine operations. The crude sonar technology of

that time used a series of three different pitches to indicate the

relative location of a target, and Johnson taught sonar operators

to sing the opening pitches of the popular Irving Berlin song White

Christmas as a guide to destroying enemy submarines. While

stationed in Key West, Florida, Johnson made his conducting debut,

leading a performance of Handel's Messiah with a volunteer

chorus and orchestra of Navy personnel and community members.

After the war, Johnson returned to Cincinnati for graduate work

in violin and composition, and also studied at the Juilliard

School and Tanglewood in the late 1940s. When Walter

Heermann left Cincinnati in 1948 to take the position of Music

Director of the MCMA, Johnson took over his post as conductor of

the college orchestra. In 1952-53, he won a Fleischmann

Fellowship, and spent a year in Europe, studying performing, and

serving as assistant to conductor Hermann Scherchen. When he

returned to America, Johnson took a position at the University of

Alabama, where he remained until leaving for Madison in

1961. At Alabama, he had a multifaceted appointment,

teaching violin and voice, conducting the chorus and orchestra,

and playing in the faculty string quartet. It was in

Alabama, that Johnson met his wife, Arline Hanke, a singer and

director of opera at the University.

Johnson's personality seems to have made him perfect fit for the

position in Madison. Genial and friendly, he was able to

work well with orchestra and chorus members and was able to

project an inviting image to the community for MCMA. Though

he was perfectly capable of being gruff and demanding in

rehearsals, his usual approach to music making was more

collaborative. He was occasionally criticized by musicians

in the orchestra for his rehearsal technique and conducting style,

but even those musicians who may have had musical differences with

Johnson express deep respect for him.

Like Prager and Heermann, Johnson also held a dual appointment as

Music Director of the MCMA and Supervisor of the Music Department

at Madison Area Technical College. Johnson had a friendly

and positive working relationship with Norman Mitby, MATC's

Director from 1960-1988, a relationship that was fundamentally

important to MCMA. Johnson worked throughout his

tenure to expand the music offerings at MATC, hiring teachers for

class piano and guitar, and teaching many classes himself.

Today at 80, Maestro Johnson is vigorous and active:

obviously enjoying his retirement and taking particular joy in his

grandchildren. He continues to conduct, recently leading the

Madison Opera's production of Brundibar, and returning to

the MSO's podium to conduct the world premiere of John Stevens's Jubilare!

to open this 75th Anniversary season. [Postscript: Roland Johnson

died in Madison on May 30, 2012 at age 91. Maestro DeMain

programmed a special work in tribute to him at the opening concert

of the 2012-13 season, the Adagio for Strings by

Madison composer John Stevens.]

|

|

MSO Pops

program, May 5, 1962

|

The Orchestra and Chorus in the 1960s and 1970s

In thinking back over his move to Madison in 1961, Johnson

remarked: "I had no idea then what a wonderful thing I was moving

into." His predecessor had left him a competent

semiprofessional orchestra and an accomplished chorus.

Though Heermann remained a respected figure, and was well-liked by

members of the orchestra, the difference in energy level between

the 71-year-old Heermann and his 41-year old successor was

palpable and MCMA's supporters were encouraged to expect great

things. According to James Crow, a longtime member of the

viola section, and eventually a president of the MCMA Board:

"There was a sort of quantum leap [in the quality of the

orchestra] right after Roland came, just as there was later when

John DeMain took over." The discipline of both

orchestra and chorus had been rather relaxed under Heermann, but

Johnson instituted much higher standards of attendance and

musicianship in both groups.

Johnson also arrived at an opportune time in the musical history

of Madison - a period of dramatic expansion at the University's

School of Music. The influx of artist-level faculty had

begun in the 1940s and 1950s, with the residency of the Pro Arte

Quartet, and the hiring of pianist Gunnar Johansen. In the

1960s, virtually every studio position at the University was

filled with musicians who were nationally-known soloists or

had played with America's major orchestras. By the 1970s,

most of the principals of the orchestra were University

faculty. In the 1970-71 season, for example, faculty

occupied the Concertmaster's chair (Thomas Moore) and principal

chairs in several other sections: viola (Martha Blum), cello

(Lowell Creitz), flute (Robert Cole), oboe (Harry Peters),

clarinet (Glenn Bowen), bassoon (Richard Lottridge), horn (Nancy

Becknell), trumpet (Donald Whitaker), trombone (Allen Chase) and

timpani (James Latimer). These faculty also brought their

students into the orchestra, and by the end of Johnson's first

decade as Music Director, the orchestra was effectively

transformed from an almost exclusively community group to an

integration of "town and gown." He also drew upon

University faculty as soloists: Johansen performed eight

times with the orchestra during Johnson's tenure, and vocalists

Bettina Bjorksten, Lois Fischer, Ilona Kombrink, Samuel Jones, and

David Hottmann were frequent soloists. In addition, most principal

chairs were given significant solos, as were pianists Leo

Steffens, Arthur Becknell, Howard Karp, and Paul Badura-Skoda.

Madison had an impressive number of fine instrumentalists and

singers who appeared as soloists. However, hiring

internationally-known soloists for the orchestra's regular

subscription programs was unusual until the later 1960s, when a

larger budget, buoyed by ticket sales and increased community and

business support made it possible. Beginning in this period,

each season would typically feature one or two "superstars."

Mezzo-soprano Shirley Verrett, alto Maureen Forrester, tenor

Richard Tucker, and baritone John Reardon were all featured

soloists in orchestra concerts of the 1960s and 1970s, as were

violinists Pinchas Zukerman, Kyung-Wha Chung, and Ruggiero Ricci,

and cellists Raya Garbousova and Zara Nelsova. Orchestra

concerts featuring pianists are always popular, and MCMA was able

to bring in some of greatest virtuosos of the day: Van

Cliburn, Mischa Dichter, John Browning, Earl Wild, James Tocco,

Claudio Arrau, Emanuel Ax, Lorin Hollander, Christina Ortiz, and

Alicia de Larrocha all appeared with the MSO during these years.

Johnson's programming took a step away from the rather

conservative approach of his predecessors. Brahms,

Tchaikovsky and Beethoven were there of course, but in the 1960s,

nearly every season featured a couple of strikingly modernist

works. Pieces by Messiaen, Schuman, Leuning and Ussachevsky

(the Concerted Piece for Tape Recorder and Orchestra),

Martin, Foss, and others were programmed in these years. The

orchestra and chorus also gave early performances to works by

established composers, in some cases, the first midwestern

performances of works that have since become standard

repertoire: Barber's Die Natali, Poulenc's Gloria,

and Britten's War Requiem. Audience reaction was

mixed, even to relatively well-established 20th-century

works. According to Robert Palmer, longtime manager of the

orchestra, "We could be chided for doing something like Bartók's Concerto

for Orchestra." However, the MCMA's programming

continued to leaven its regular mix of standard Classical and

Romantic repertoire with a liberal sprinkling of more adventurous

works.

Premieres were nothing new in the history of the orchestra, but

works by Sigfrid Prager, Sybil Hanks, Oskar Hagen and others

premiered by the orchestra through the 1950s were hardly pieces of

the avant garde. Johnson actively sought out commissions,

and premiered some eighteen works with MCMA's groups,

culminating with the Madison Opera's performance of Shining

Brow. The orchestra also gave first performances of works by

Lee Hoiby, Robert Crane, Stephen Chatman, Alec Wilder, Gunnar

Johansen, John Harbison, Crawford Gates, and Michael

Torke. Boston-based Gunther Schuller had a

particularly close relationship with the MCMA, founded on a

longstanding friendship with Johnson. The orchestra

premiered three of his works and gave early performances to three

others. Johnson's final commission for the orchestra and

chorus was Daron Hagen's Joyful Music, performed at the

holiday concert in 1993, and revived again for this season's

"Holiday Spectacular."

live performance on WHA-TV in 1974

By the end of Heermann's

tenure, the annual routine of MCMA programs was

well-established: a yearly series of four free concerts, two

of which would include the chorus, and a spring Pops

program. The tradition of an annual Young People's program,

reinstituted by Heermann in 1949, had quietly lapsed during the

late 1950s. In Johnson's first season, the MCMA's regular

series expanded to five concerts, and the number and types of

programs performed each season steadily expanded over the next 20

years. In particular, the MCMA began a tradition of

community outreach with widely-varied programming. In the later

1960s and 1970s, for example, Johnson established a series of

"Neighborhood Family Concerts," designed to get the

orchestra out of the downtown area and into other parts of the

city. These programs, held at a different local high school

each season, featured light repertoire designed to be inviting for

families. Many programs were broadcast by Wisconsin Public

Radio, and in the middle 1970s, the orchestra was featured in two

live broadcast concerts from the studio of Wisconsin Public

Television.

By the end of Heermann's

tenure, the annual routine of MCMA programs was

well-established: a yearly series of four free concerts, two

of which would include the chorus, and a spring Pops

program. The tradition of an annual Young People's program,

reinstituted by Heermann in 1949, had quietly lapsed during the

late 1950s. In Johnson's first season, the MCMA's regular

series expanded to five concerts, and the number and types of

programs performed each season steadily expanded over the next 20

years. In particular, the MCMA began a tradition of

community outreach with widely-varied programming. In the later

1960s and 1970s, for example, Johnson established a series of

"Neighborhood Family Concerts," designed to get the

orchestra out of the downtown area and into other parts of the

city. These programs, held at a different local high school

each season, featured light repertoire designed to be inviting for

families. Many programs were broadcast by Wisconsin Public

Radio, and in the middle 1970s, the orchestra was featured in two

live broadcast concerts from the studio of Wisconsin Public

Television.

In 1962, Johnson reinstituted the annual Youth program with a

tremendously successful concert featuring beloved TV personality

Captain Kangaroo, beginning an unbroken series of annual youth

concerts that has continued to the present day. In the

1966-67 season, the orchestra began to offer two youth programs

each year. Funding and promoting youth programming became

one of the main missions of the Madison Symphony Orchestra League

(MSOL, formerly known as the Women's Committee). Youth

soloists were occasionally featured in these programs, but in 1974

Evelyn Steenbock, a great supporter of both the orchestra's youth

programs and the Wisconsin Youth Symphony Orchestra, established

an endowment for an annual competition and scholarship award for

promising young instrumentalists. The first "Steenbock

Awards Program" in April 1974 featured three young soloists -

pianists David Askins and Tania Heiberg, and violinist Sharan

Leventhal - and dozens of young musicians were featured at these

springtime concerts in succeeding seasons. In 1986, a

parallel competition, the Youth Soloist Awards was established to

showcase young musicians at the annual Fall Youth Concerts.

Many of the musicians who have been featured soloists at the MSO's

youth concerts have gone on to successful musical careers, and

four of them - Cynthia Bittar, Laura Burns, Katie Kretschman and

Annaliese Kowert - are in the ranks of the orchestra in the

2000-2001 season.

Since 1940, all of MCMA's concerts, with the exception of the

annual benefit Pops programs, had been offered to the public free

of charge. Any change in this well-established tradition was

bound to be controversial, but by the middle 1960s, it was

increasingly apparent that the orchestra and chorus would need to

begin charging for their programs if MCMA was to continue

growing. In the 1966-67 season, the two choral programs were

ticketed, while orchestra programs remained free. In the

following season, it was necessary to purchase tickets all of

MCMA's regular series. It was at this same time that

the orchestra underwent a name change: since 1926, it had

been known as the Madison Civic Symphony, but in 1966, it was

officially designated the Madison Symphony Orchestra. The

MCMA's chorus retained its "Civic" designation for several more

years, until it was finally renamed the Madison Symphony Chorus in

the 1983-84 season.

The Pops tradition that began in Heermann's last years continued

in the 1960s: the venue moved to the Dane County Youth Building,

and the concert became a large-scale fundraising event for the

MSOL. The concerts themselves became more "upscale,"

featuring nationally-known artists, either as soloists or guest

conductors. The May 1968 program, for example, was lead by

Mitch Miller, whose Sing Along With Mitch variety show had

been a television hit all through the 1950s and early 1960s.

Virtually every Pops concert after that featured star

performers: William Walker, Leroy Anderson, Peter Nero,

Benny Goodman, Sarah Vaughan, Marvin Hamlisch, and others appeared

with the MSO in Pops programs over the next decade.

Johnson worked much more actively with the chorus than his

predecessor, and expanded its role. He had worked for several

years as a choral conductor in Alabama, and was obviously

comfortable working in this very different medium. By tradition

begun in the 1930s, Handel's Messiah was an annual event,

but Johnson broke with this tradition early in the 1960s to explore

other great choral works. Messiah was still heard once

every two or three seasons, but December chorus and orchestra

concerts began to feature a much broader repertoire: works by

Schütz, Britten, Respighi, Vaughan Williams, Bach, and others.

Johnson also began to program a major choral work on the closing

concert of nearly every season. By the late 1970s and 1980s,

the chorus usually appeared in three programs each season, twice on

the subscription series, and in a special choral concert presented

in the late spring, typically a program dedicated to the works of a

single composer.

January 1971 program

in the Masonic Temple Auditorium

(Soloist Ilona Kombrink singing Ravel's Shéhérezade)

One of the most important

changes in the workings of the MCMA during Johnson's tenure was the

development of a professional support staff. Until the 1960s,

the non-musical activities of MCMA - marketing, fundraising, ticket

sales, etc. - had been handled by volunteers. During the

1950s, a volunteer from the Board, Helen Supernaw, was in essence

the entire "staff" of the MCMA. This situation continued in

the early 1960s: Helen Hay, who arrived in town at about the same

time as the Johnsons, took over from Supernaw as the manager of the

orchestra's day-to day activities, staffing the office, and even

publishing the MCMA's newsletter Variations on the Theme of

Civic Music. Hay, Ann Crow, and other volunteers handled

virtually everything. With a budget that was rapidly

burgeoning in the mid 1960s, the situation began to change. A few

years later, over the objection of Hay, who was "perfectly happy"

working as a volunteer, the Board converted her unofficial job to a

part-time, paid position, in anticipation of continued growth and

the need for a professional staff as a regular part of the annual

budget. Hay eventually stepped aside from the management of

the orchestra, but continued to work as a volunteer in many

areas. The first full-time Manager of the MCMA was

John Reel, who served for two seasons, from 1968-1970. He was

succeeded by Winifred Cook, Manager from 1970-1975. In 1972,

the staff expanded to two with the hiring of Jean Feige as

secretary, a position she held for over twenty years.

One of the most important

changes in the workings of the MCMA during Johnson's tenure was the

development of a professional support staff. Until the 1960s,

the non-musical activities of MCMA - marketing, fundraising, ticket

sales, etc. - had been handled by volunteers. During the

1950s, a volunteer from the Board, Helen Supernaw, was in essence

the entire "staff" of the MCMA. This situation continued in

the early 1960s: Helen Hay, who arrived in town at about the same

time as the Johnsons, took over from Supernaw as the manager of the

orchestra's day-to day activities, staffing the office, and even

publishing the MCMA's newsletter Variations on the Theme of

Civic Music. Hay, Ann Crow, and other volunteers handled

virtually everything. With a budget that was rapidly

burgeoning in the mid 1960s, the situation began to change. A few

years later, over the objection of Hay, who was "perfectly happy"

working as a volunteer, the Board converted her unofficial job to a

part-time, paid position, in anticipation of continued growth and

the need for a professional staff as a regular part of the annual

budget. Hay eventually stepped aside from the management of

the orchestra, but continued to work as a volunteer in many

areas. The first full-time Manager of the MCMA was

John Reel, who served for two seasons, from 1968-1970. He was

succeeded by Winifred Cook, Manager from 1970-1975. In 1972,

the staff expanded to two with the hiring of Jean Feige as

secretary, a position she held for over twenty years.

The staffer who had the greatest impact on the growth of the MCMA

in this period, however, was Robert Palmer, who served as Manager

from 1975 until 1992. A rather relaxed administrator, Palmer

was nevertheless able to market the orchestra in an effective way,

and oversaw unprecedented growth in budget and orchestral

activities in this period. Palmer also brought a tremendous

knowledge of repertoire and a good musical ear to the

organization. He was generally respected by the members of an

increasingly professionalized orchestra, and became a trusted

partner of Johnson's in musical matters as well. Palmer was

also capable of adapting to changes in the orchestra's situation,

particularly the move to the Oscar Mayer Theatre in 1980. In

an interview, Palmer admitted to being quite hesitant in the late

1970s about the Civic Center—in his words, "I was a soothsayer of

doom and gloom." However, when it became obvious not only

that the Oscar Mayer was going to work as a venue, but that it

presented tremendous opportunities for new programming, he

directed his efforts towards exploiting those possibilities.

He pointed with pride, for example, to the enormous all-Wagner

concert that opened the 1983-84 season as an example of

programming that would have been impossible previously. In

looking back over his tenure as Manager, Palmer refers to it as a

"labor of love," and expressed his pleasure at the orchestra's

continued success. Palmer's successor, Sandra Madden,

brought a much more businesslike approach to management of the

orchestra. Under Madden, the administrative staff continued

to expand, with full-time professional marketing,

development/fundraising, and orchestra management personnel.

An even more fundamental change was the increasingly professional

status of the orchestra. With persistent prodding from

Heermann in the 1950s, the MCMA had made some hesitant initial

steps towards paying a few members of the orchestra, and

Musician's Union members were paid for performances by the

Musician's Performance Trust Fund (MPTF). Johnson

aggressively pursued this issue 0 he states that one of the very

first "courtesy calls" he made after moving to Madison was to the

local Union secretary, to explore ways of expanding pay for

orchestra members. Within a year, most orchestra

members were paid a modest honorarium by the MCMA, under the guise

of "baby-sitting money" and MPTF funds continued to fund

concerts. By 1970, everyone in the orchestra was paid on a

"per service" basis by the MCMA for rehearsals and concerts, on a

sliding scale that was dependent on ranking within sections and

Union status. Union membership was never a

requirement, but the local Union did play a limited role in

contract negotiations in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1993, the

Orchestra Committee, an elected body from the ranks of the

orchestra, negotiated directly with MCMA to conclude a renewable

three-year Master Agreement that remains the basis of the

orchestra's contract today. The effect of pay on the

orchestra was immeasurable. Johnson attributes much of the

great increase in the quality of the orchestra's playing in the

late 1960s and 1970s to the influx of fine players, but also to

this change in status: "You could see how much it changed

their outlook and the pride that everyone took in what they were

doing."

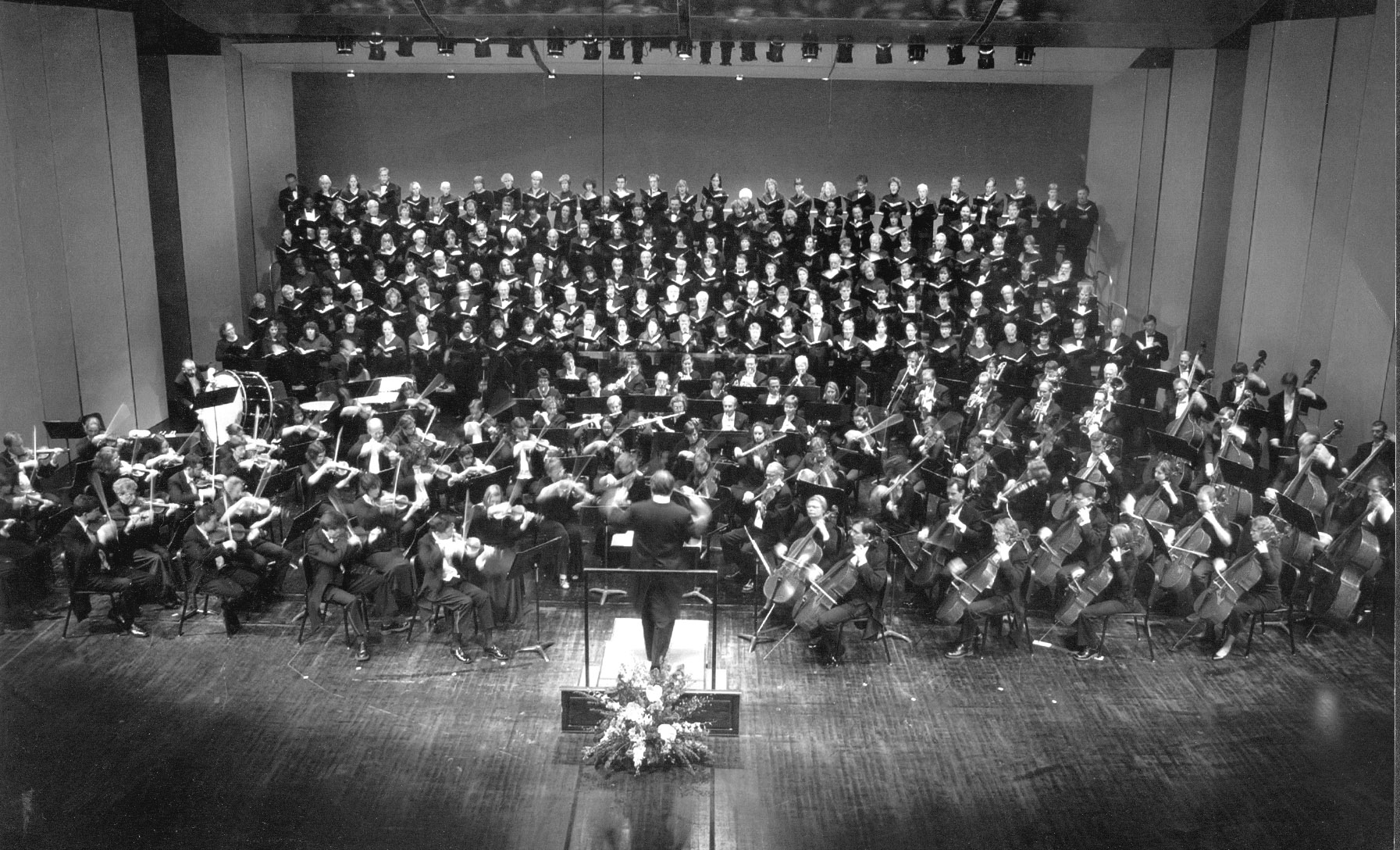

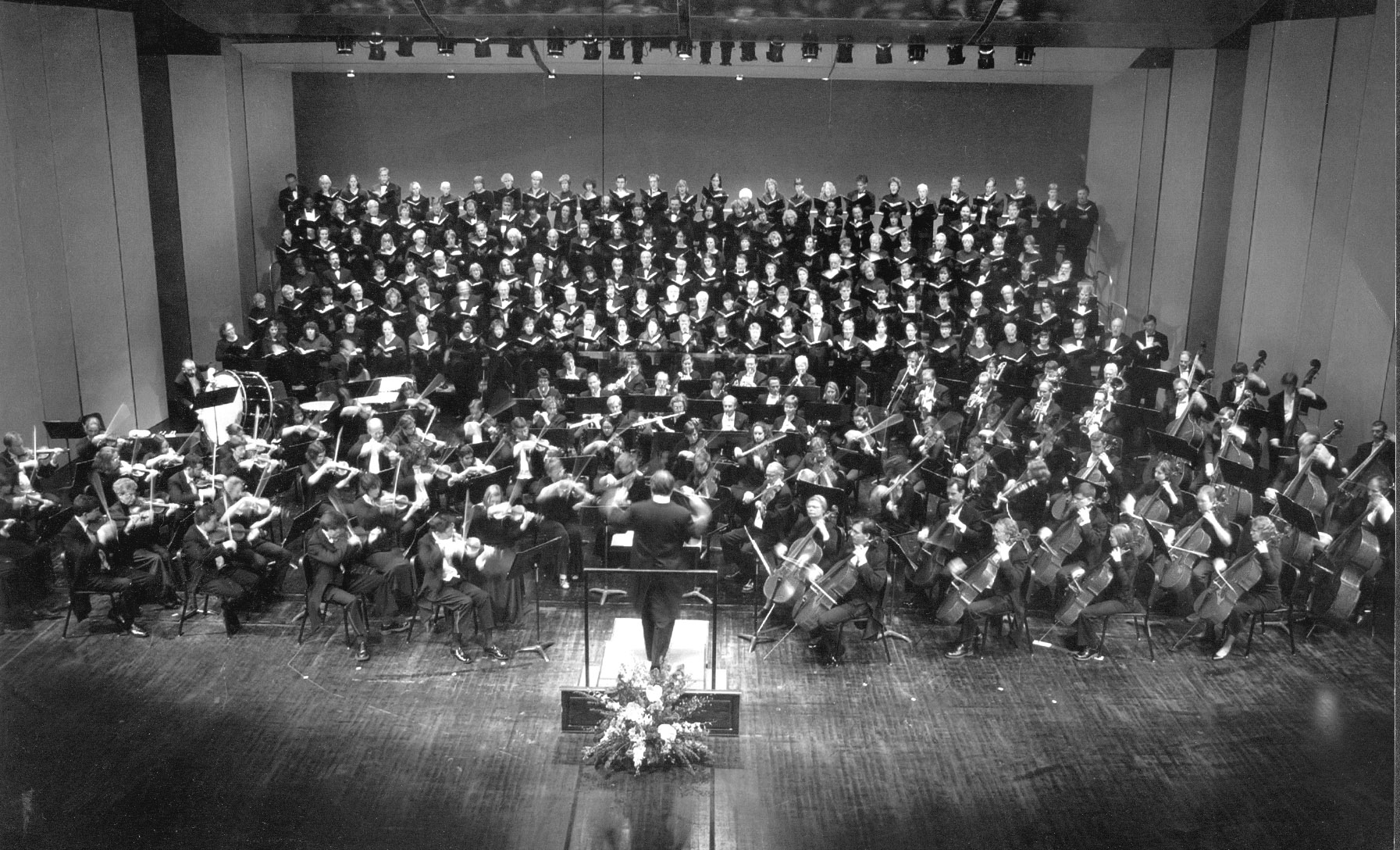

concert in the Oscar

Mayer Theater, 2003 (under John DeMain)

A New

Venue

A New

Venue

Another change occurred in 1980, with the completion of the

Madison Civic Center. The search for an adequate performance

space was ancient history by the time Johnson arrived in

Madison. Under Prager, orchestra concerts had moved

constantly from venue to venue, settling more or less permanently

into the attractive but boomy confines of the Masonic Temple

Auditorium in the late 1930s. Under Heermann, the orchestra

and chorus had performed almost exclusively on the cramped stage

of the Central High School Auditorium. This space, which was

later renovated and renamed MATC Auditorium, remained the

orchestra's primary home through the 1960s and 1970s, but Johnson

occasionally moved concerts to the Masonic Temple or the

University Stock Pavilion. Though the Stock Pavilion had

fine acoustics and could seat many more audience members than any

other space in town, it was impossible to forget that the primary

purpose of this building was not music. This was especially

apparent during one of soprano Eileen Farrell's visits to Madison,

recalls Johnson. She arrived in 1969 to do a concert with

the orchestra, which was moved to the Stock Pavilion to

accommodate a large crowd. When the orchestra arrived for

the dress rehearsal, they found that someone had neglected to move

a large wagon filled with very ripe manure, at the far end of the

hall, but still "stinking to high heaven." When she arrived

at the rehearsal, Johnson apologized profusely to Farrell about

the smell. According to Johnson, she was a consummate

professional about the whole thing until she started to giggle

uncontrollably during the first number (the aria "Ritorna

vincitor" from Aida), eventually breaking down completely,

and commenting that "At least my vocal chords are being

well-fertilized."

The Madison Civic Center was part of Madison's urban renewal

efforts in the 1970s: every bit as much a contentious political

issue in its day as today's Overture Project. The Civic

Center was constructed around the Capitol Theater, a 2000-seat

auditorium built in the 1920s, the heyday of Vaudeville and silent

movies. Renovated as the Oscar Mayer Theatre, a

multipurpose hall, this space became the orchestra's home.

The MSO inaugurated the new hall on February 23, 1980, with a gala

concert that featured soprano Martina Arroyo, and a performance of

Beethoven's Symphony No.9. While some of the

acoustical problems of the Oscar Mayer Theatre became obvious

immediately, this new hall opened up enormous new possibilities

for the orchestra. The stage of MATC Auditorium was simply not big

enough to accommodate a large chorus and orchestra. MATC

Auditorium also severely limited the size of the audience:

most MSO concerts in the late 1970s were given twice to

accommodate more audience members. With a stage more than

double the size of MATC, the Oscar Mayer Theatre could hold the

large forces - 300 or more musicians - necessary to perform works

like the Verdi Requiem or Prokofiev's Alexander Nevsky

Cantata. The string section grew by several

players within a few years of the move to the Civic Center, and

the chorus grew as well. Like the change to professional

status, the move to the new hall - a grandly designed and

impressive space, despite its shortcomings - also had the effect

of kindling pride in orchestra and increasing musical quality.

Opera in Madison

When the Johnsons arrived in Madison in 1961, many of the singers

associated with MCMA wanted to resurrect the tradition of staged

opera in the city. Prager lead fully staged annual productions for

six years during the 1930s, but the tradition languished during

the war years. In the later 1950s, Heermann had begun to

program "concert versions" of operas using mostly local

soloists. The team of Roland and Arline Johnson came

prepared with an enormous amount of background in opera.

Roland had conducted several works while in Alabama, and Arline

was already a noted stage director. Lois Dick, Robert

Tottingham, Warren Crandall, Joanna Overn, and other Civic Chorus

members approached the Johnsons to ask for their leadership in

creating an opera company under the auspices of MCMA.

The first production was not a staged affair: members of

the newly-created Madison Civic Opera Workshop sang the second act

of Johann Strauss's Die Fledermaus at the annual Pops

concert in May of 1962. Audience response to this

performance, which was the finale of a program called "A Night in

Vienna," was enthusiastic enough to warrant a more ambitious

production the next season. The Opera Workshop was

reorganized as the Madison Civic Opera Guild, and the organization

became another distinct group under the umbrella of MCMA. Unlike

the its companion organizations the Symphony and Chorus, the Opera

Guild had its own Advisory Board, and always maintained a degree

of independence from MCMA

. (Some thirty years later, the division became formal with the

incorporation of the Madison Opera.) In March of 1963, the Opera

Guild staged La Boheme at the East High School

Auditorium. This was the first of an unbroken annual series

of successful staged performance. By 1967, demand was such

that a staged revival of Die Fledermaus played for six

performances, three of them out of town. Arline Johnson

remained the Opera's stage director until her death in 1988.

Ann Stanke, a member of the orchestra since the 1950s, and long an

opera supporter and rehearsal pianist for the Johnsons'

productions, took an ever-larger role in the operations of the

company, eventually presiding over the Madison Opera's separation

from the Symphony.

The Opera's growth during the Johnson years paralleled developments

in the Symphony. Virtually all of the soloists in the 1960s

and early 1970s were local singers and University faculty members

volunteering their time. The early years featured pieces from

the standard repertoire - Tosca, Falstaff, Carmen, and other

familiar works - but there was also a rather adventurous

experimental side, as the company performed several relatively

obscure works: Britten's Noye's Fludde (1963),

Poulenc's Voix Humaine (1964), The Jumping Frog of

Caleveras County by Lukas Foss (1968), and Douglas Moore's

The Ballad of Baby Doe (1969). In 1974, the

company moved into a more professional venue, the Wisconsin Union

Theater, and hired its first out-of-town soloist, Milwaukee-based

tenor Daniel Nelson. Nelson sang the role of Pinkerton in Madame

Butterfly, and appeared in several subsequent Opera and

Symphony performances. In 1980, the Opera mounted two

performances of Aďda in the Oscar Mayer Theatre, as part of

celebrations for the newly-opened Civic Center. This

production of Aďda, the grandest of all grand operas, was

something of a landmark: certainly the most ambitious

performance the Opera had attempted to that time, their first

performance in Italian, and the first production that featured

internationally-known soloists, most notably Lorna Haywood and

Marvelee Cariaga. This performance also marked the company's

first widespread attention on the national scene, with favorable

notices in Opera News.

Johnson's last years as Music Director and Shining Brow

By the 1990s, the Madison Symphony Orchestra was recognized as one

of America's leading regional orchestras. The quality of the

orchestra's playing had reached a relatively high plateau: the

woodwinds and brass, led in most sections by University studio

faculty, were particularly good. The string section, much

larger than it was in the early 1960s

- but still too small by most accounts to balance the back half of

the orchestra

- was occasionally criticized for ensemble and intonation

problems. Though the quality of MSO performances could

occasionally be uneven, the ensemble was capable of excellent

playing and several particularly fine performances from this

period stand out in this writer's memory: Hindemith's Symphonic

Metamorphoses and Brahms's Symphony No.4 in the

1990-91 season, the Dvorák Symphony No.8, Brahms's Violin

Concerto (with Itzhak Perlman), and the Bach Mass in B

minor, all from the 1991-92 season, and a thoroughly

enjoyable performance of Prokofiev's Alexander Nevsky film

music with the film itself in 1994. According to

Johnson, "...[by then] the orchestra was capable of playing just

about anything I put in front of them." The number of

subscription programs had increased to eight, and the orchestra

performed two Youth concerts, two Pops programs, and numerous

special and Opera performances each season.

Premieres and contemporary music had long been part of the

orchestra's repertoire, but attempting to mount a newly-composed

grand opera was not in the realm of possibility until 1988.

This was the very period when Frank Lloyd Wright's "Dream Civic

Center," designed fifty years earlier was once again under public

discussion in the city. After several attempts to fund and

build the project, Wright's proposed Civic Center had failed in

1962. In the late 1980s, Wright's design

- possibly reconfigured as a convention center

- was once again on the table. The idea to create an opera

based upon Wright's life can be attributed to Terry Haller and

Marvin Woerpel, members of the Madison Opera's Advisory Board, but

Johnson also took up the challenge with enthusiasm. At

Johnson's urging, MCMA's Madison Opera selected a young

Milwaukee-born composer named Daron Hagen, and Hagen in turn

contacted Princeton University poet Paul Muldoon about writing a

libretto. Another hurdle was to get permission from the

Wright Foundation, a process that took nearly a year.

Roland Johnson in 1994

The highest hurdle was

financial: the decision to mount Shining Brow was a risky

one. While the cost of Madison Opera's productions had risen

significantly during the 1980s, this was another order of expense

altogether: commissioning fees for composer and librettist,

hiring a cast of nationally-known singers and a first-rank stage

director (Stephen Wadsworth), set and costume design, and extra

rehearsals needed to negotiate Hagen's difficult orchestral

parts. In the end, Madison Opera raised nearly

$500,000

- approximately eighty times the entire budget of MCMA when

Johnson arrived in 1961

- from private donors, businesses, and foundations, including a

prestigious grant from Opera America.

The highest hurdle was

financial: the decision to mount Shining Brow was a risky

one. While the cost of Madison Opera's productions had risen

significantly during the 1980s, this was another order of expense

altogether: commissioning fees for composer and librettist,

hiring a cast of nationally-known singers and a first-rank stage

director (Stephen Wadsworth), set and costume design, and extra

rehearsals needed to negotiate Hagen's difficult orchestral

parts. In the end, Madison Opera raised nearly

$500,000

- approximately eighty times the entire budget of MCMA when

Johnson arrived in 1961

- from private donors, businesses, and foundations, including a

prestigious grant from Opera America.

Some three years in the making, Shining Brow was a

challenging work, dealing with the most tumultuous years in

Wright's career. Michael Sokol was given the complex role of

Wright himself, and Carolanne Page created the role of his lover

Mamah Cheney. The orchestral parts were particularly

difficult, featuring virtuoso passages for nearly every

instrument. The premiere on April 21, 1993 was a great

success. Critics from across the country attended the

performance, and reviews were generally very favorable:

Muldoon's rather densely-constructed libretto came in for

criticism from some quarters, but Hagen's music, resplendent with

quotations, allusions, and, most importantly, good tunes was

applauded by nearly every critic. In particular, reviewers

praised the quality of the performance, both on stage and in the

pit, and lauded the "plucky little company" that took on the

monumental task of putting it on stage. One side benefit for

the orchestra in particular was the forging of a close

relationship with Daron Hagen, who would compose three more works

for the MSO.

It is obvious that Maestro Johnson considered Shining Brow

to be a valedictory achievement: in March of 1992, when the

opera was just notes on paper, he announced his forthcoming

retirement at the close of the 1993-94 season. Johnson's 33

seasons as MCMA's Music Director - nearly half of the orchestra's

75 years - saw an almost total transformation of the Madison

Symphony Orchestra as an institution. In 1961, the MCMA's

groups were a venerable amateur institution in Madison:

though Sigfrid Prager had long since left the scene, his vision of

the orchestra as a largely volunteer civic organization was still

the ruling concept. By Johnson's retirement in 1994,

the orchestra was a fully professional regional

institution. Among musicians, community members, and

critics alike, Maestro Johnson has been given the lion's share of

credit for this transformation.

-------

©2000 J. Michael Allsen - revised 2015 and 2020

last update: 10/17/20

Roland Johnson

Roland Johnson

By the end of Heermann's

tenure, the annual routine of MCMA programs was

well-established: a yearly series of four free concerts, two

of which would include the chorus, and a spring Pops

program. The tradition of an annual Young People's program,

reinstituted by Heermann in 1949, had quietly lapsed during the

late 1950s. In Johnson's first season, the MCMA's regular

series expanded to five concerts, and the number and types of

programs performed each season steadily expanded over the next 20

years. In particular, the MCMA began a tradition of

community outreach with widely-varied programming. In the later

1960s and 1970s, for example, Johnson established a series of

"Neighborhood Family Concerts," designed to get the

orchestra out of the downtown area and into other parts of the

city. These programs, held at a different local high school

each season, featured light repertoire designed to be inviting for

families. Many programs were broadcast by Wisconsin Public

Radio, and in the middle 1970s, the orchestra was featured in two

live broadcast concerts from the studio of Wisconsin Public

Television.

By the end of Heermann's

tenure, the annual routine of MCMA programs was

well-established: a yearly series of four free concerts, two

of which would include the chorus, and a spring Pops

program. The tradition of an annual Young People's program,

reinstituted by Heermann in 1949, had quietly lapsed during the

late 1950s. In Johnson's first season, the MCMA's regular

series expanded to five concerts, and the number and types of

programs performed each season steadily expanded over the next 20

years. In particular, the MCMA began a tradition of

community outreach with widely-varied programming. In the later

1960s and 1970s, for example, Johnson established a series of

"Neighborhood Family Concerts," designed to get the

orchestra out of the downtown area and into other parts of the

city. These programs, held at a different local high school

each season, featured light repertoire designed to be inviting for

families. Many programs were broadcast by Wisconsin Public

Radio, and in the middle 1970s, the orchestra was featured in two

live broadcast concerts from the studio of Wisconsin Public

Television. One of the most important

changes in the workings of the MCMA during Johnson's tenure was the

development of a professional support staff. Until the 1960s,

the non-musical activities of MCMA - marketing, fundraising, ticket

sales, etc. - had been handled by volunteers. During the

1950s, a volunteer from the Board, Helen Supernaw, was in essence

the entire "staff" of the MCMA. This situation continued in

the early 1960s: Helen Hay, who arrived in town at about the same

time as the Johnsons, took over from Supernaw as the manager of the

orchestra's day-to day activities, staffing the office, and even

publishing the MCMA's newsletter Variations on the Theme of

Civic Music. Hay, Ann Crow, and other volunteers handled

virtually everything. With a budget that was rapidly

burgeoning in the mid 1960s, the situation began to change. A few

years later, over the objection of Hay, who was "perfectly happy"

working as a volunteer, the Board converted her unofficial job to a

part-time, paid position, in anticipation of continued growth and

the need for a professional staff as a regular part of the annual

budget. Hay eventually stepped aside from the management of

the orchestra, but continued to work as a volunteer in many

areas. The first full-time Manager of the MCMA was

John Reel, who served for two seasons, from 1968-1970. He was

succeeded by Winifred Cook, Manager from 1970-1975. In 1972,

the staff expanded to two with the hiring of Jean Feige as

secretary, a position she held for over twenty years.

One of the most important

changes in the workings of the MCMA during Johnson's tenure was the

development of a professional support staff. Until the 1960s,

the non-musical activities of MCMA - marketing, fundraising, ticket

sales, etc. - had been handled by volunteers. During the

1950s, a volunteer from the Board, Helen Supernaw, was in essence

the entire "staff" of the MCMA. This situation continued in

the early 1960s: Helen Hay, who arrived in town at about the same

time as the Johnsons, took over from Supernaw as the manager of the

orchestra's day-to day activities, staffing the office, and even

publishing the MCMA's newsletter Variations on the Theme of

Civic Music. Hay, Ann Crow, and other volunteers handled

virtually everything. With a budget that was rapidly

burgeoning in the mid 1960s, the situation began to change. A few

years later, over the objection of Hay, who was "perfectly happy"

working as a volunteer, the Board converted her unofficial job to a

part-time, paid position, in anticipation of continued growth and

the need for a professional staff as a regular part of the annual

budget. Hay eventually stepped aside from the management of

the orchestra, but continued to work as a volunteer in many

areas. The first full-time Manager of the MCMA was

John Reel, who served for two seasons, from 1968-1970. He was

succeeded by Winifred Cook, Manager from 1970-1975. In 1972,

the staff expanded to two with the hiring of Jean Feige as

secretary, a position she held for over twenty years.

A New

Venue

A New

Venue  The highest hurdle was

financial: the decision to mount Shining Brow was a risky

one. While the cost of Madison Opera's productions had risen

significantly during the 1980s, this was another order of expense

altogether: commissioning fees for composer and librettist,

hiring a cast of nationally-known singers and a first-rank stage

director (Stephen Wadsworth), set and costume design, and extra

rehearsals needed to negotiate Hagen's difficult orchestral

parts. In the end, Madison Opera raised nearly

$500,000

- approximately eighty times the entire budget of MCMA when

Johnson arrived in 1961

- from private donors, businesses, and foundations, including a

prestigious grant from Opera America.

The highest hurdle was

financial: the decision to mount Shining Brow was a risky

one. While the cost of Madison Opera's productions had risen

significantly during the 1980s, this was another order of expense

altogether: commissioning fees for composer and librettist,

hiring a cast of nationally-known singers and a first-rank stage

director (Stephen Wadsworth), set and costume design, and extra

rehearsals needed to negotiate Hagen's difficult orchestral

parts. In the end, Madison Opera raised nearly

$500,000

- approximately eighty times the entire budget of MCMA when

Johnson arrived in 1961

- from private donors, businesses, and foundations, including a

prestigious grant from Opera America.